rmarcksharpdown

This is an R Markdown document…

library(tidyverse)

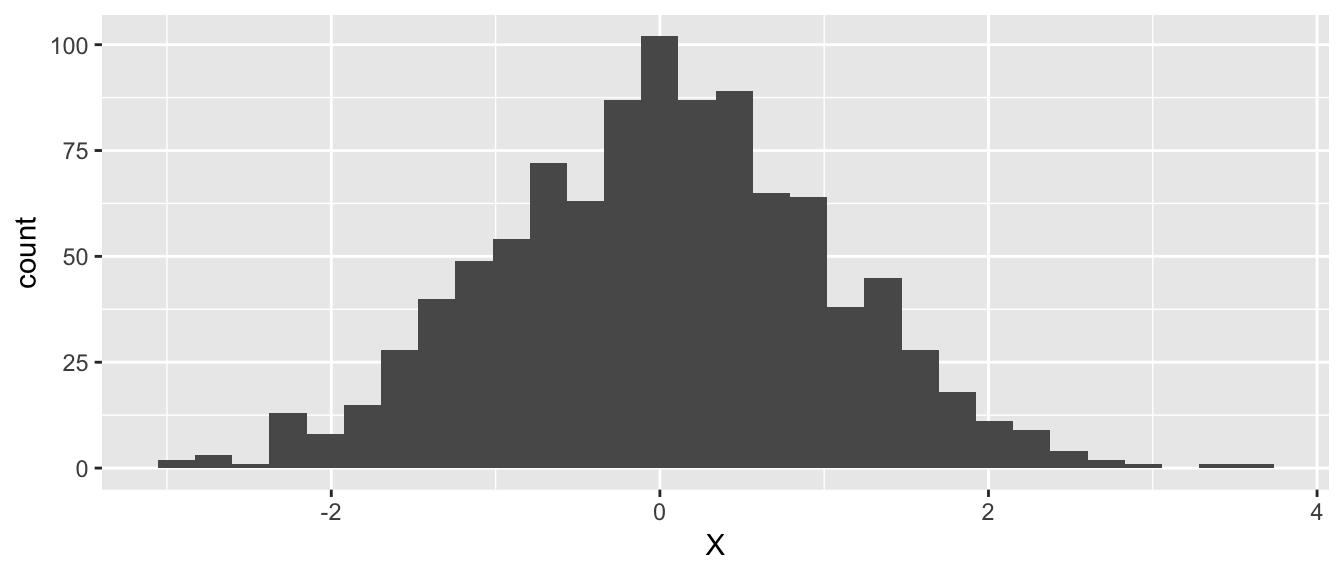

data_frame(X = rnorm(1000)) %>%

ggplot(aes(X)) +

geom_histogram()

And this is some c# code…

Console.WriteLine("Hello World!");# Hello World!🤩 …that the document just executed! 🤩

And here’s some more c# code that talks across different Rmd code blocks…

var greatDay = "What a great day!";greatDay = greatDay + " I hope yours is good too! ❤️🧡💚💙💜";Console.WriteLine(greatDay);# What a great day! I hope yours is good too! ❤️🧡💚💙💜You can define functions…

public static void DoIt()

{

Console.WriteLine("It's Done!");

}And call them later…

DoIt()# It's Done!You want classes?

public class MathClass

{

public int WhatsTwoPlusTwo()

{

return 4; //Pretty sure that's right

}

}You got classes.

var m = new MathClass();

m.WhatsTwoPlusTwo()# 4How’d You Do It?

Some duct tape. A lot less than I thought when I started. R Markdown runs on knitr, and knitr exposes some ducts you can tape (they’re called engines) so the code in code blocks can be passed to different compilers and interpreters.

An engine is a function that takes options, runs the code in options$code through whatever program you want, and then (most simply) calls a wrapper function for output from code blocks called knitr::engine_output that puts the results in the document.

Here’s the code from the setup chunk of this post. First we load up the libraries we’re going to need.

library(uuid)

library(subprocess)

knitr::opts_chunk$set(echo = TRUE, cache=FALSE, warning = FALSE, message = FALSE)uuid gives us uuids. subprocess is a package that allows you to run and control subprocesses from R. It gives you a handle for a process that lets you write to its stdin and read its stdout/stderr. What process are we going to run?

dn = "/usr/local/share/dotnet-script/dotnet-script"

handle = spawn_process(dn)

Sys.sleep(1)dotnet-script lets you run c# scripts from the command line. This whole deal wouldn’t be possible without it. What are we going to do with it? We run it here at the top level (outside of the engine function) so that we have a interpreter session that lives for the whole rendering process. This lets later chunks use variables/functions/etc declared in earlier chunks.

The Engine

cs_engine = function(options) {

done_signal = uuid::UUIDgenerate()

#print(paste("done", done_signal))

if (length(options$code) == 1) {

process_write(handle, paste0(options$code, '\nConsole.WriteLine("', done_signal, '");\n'))

} else {

process_write(handle, paste0(paste(options$code, collapse = "\n"), '\nConsole.WriteLine("', done_signal, '");\n'))

}

out = ""

while(TRUE) {

on_the_way_in = process_read(handle, timeout = 1000)$stdout

out = paste0(out, on_the_way_in)

if (any(grepl(done_signal, out))) {

#print("FOUND IT!")

#print(out)

break

}

#print("No Done Signal Yet.")

#print(out)

}

knitr::engine_output(options, options$code, str_replace_all(out, done_signal, ""))

}

knitr::knit_engines$set(cs = cs_engine)In this code we define the cs_engine function and hook it up to knitr. cs_engine gets called on each code chunk in the Rmd marked with {cs} (instead of {r}) and does the following:

- Create a “done!” signal. We have no idea what the code in each chunk is going to do or how long it’s going to take, so we need some kind of signal that dotnet-script can give us so we know it’s finished what we gave it. The done signal is a uuid.

options$codeis a vector of strings, we need to package it up into text to pass to dotnet-scripts stdin. After the last line of code from the chunk we add a line to write the “done!” signal.- We call

process_write(handle, ...)to write the code to dotnet-script’s stdin. - We’ve written all the code for the chunk, now we’re waiting for a response from dotnet-script. We loop, calling

process_read(handle, ...)and pull$stdoutto get everything that was printed out. Everytime we get some response we check it for the done signal. If we find the done signal we break out of the loop. - Strips the “done!” signal from the output and calls

knitr::engine_outputto write the full response to the document.

In addition to this R code I had to make some changes to dotnet-script to allow it to be driven from stdin like this. I’m not sure they’re the best changes (or ones the maintainer would accept), but they can be found here and they do pass all the previously written tests on linux, mac, and windows :).